Brehanna Daniels, Racing

Brehanna Daniels loses her mother in high school, channeling her grief into basketball. At Norfolk State University - where 5'4" Brehanna averages 13.9 points per game - she’s approached to try-out for the NASCAR Drive for Diversity pit crew development program. Brehanna knows nothing about the historically white, male-dominated sport but feels strongly she must go for it. The only female to show up, she aces the test, then kills it at the combine to become the first African-American woman to go over the wall in a national racing series and work a NASCAR pit crew, including the prestigious Cup series. Brehanna’s goals are to be the first African-American to pit the Daytona 500 and become a movie star. No problem.

Bertha Benz, Entrepreneur

Summer of 1888. Bertha Benz steals a car with her sons, leaves a note, drives 65 miles on roads barely fit for horses, fixes the ignition with her garter, unclogs a fuel line with a hairpin, invents brake pads, convinces pharmacists to give her ligroin for fuel, pushes the car when it runs out, gives test drives. Almost 12 hours later, Bertha telegraphs the owner/inventor — her husband, Karl — but word has already spread. Her plan to drum up interest in the “smoking monster” that would still be sitting in her garage today works and Bertha — whose birth warrants the entry “Unfortunately, only a girl again” in the family bible — launches a machine that changes the world. Drop the mic.

Danica Patrick, Racing

Some call Danica Patrick a gimmick. She’s kart racing by age ten, winning her class three times in the mid-90s. Nailing Rookie of the Year for both the 2005 Indianapolis 500 and 2005 IndyCar Series, she finishes 3rd at Indianapolis 500, the best for a woman. She wins the 2008 Indy Japan 300, the only female to win an IndyCar Series race. In 2014, she’s the first woman to win a pole position in the Toyota Atlantic Series. She retires in 2018 having surpassed Janet Guthrie’s record for the most top-ten finishes by a woman in the Sprint Cup Series, the highest female finisher in both the Indianapolis and Daytona 500’s and one of only 14 drivers to lead both races. Gimmick? Sure.

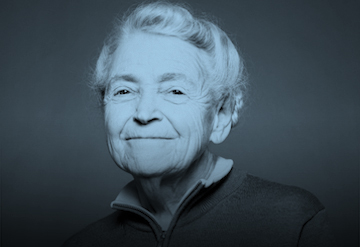

Denise McCluggage, Journalist

Born in Eldorado, Kansas, Denise McCluggage moves west to attend Mills College in Oakland, California, joining the San Francisco Chronicle after graduation. She first covers “women’s” stories and soon discovers her love of what becomes known as extreme sports — skiing, racing, skydiving. Denise convinces her editors she’s better able to cover races as a driver — women are not allowed in the pits or the paddock — and pioneers participatory sports journalism. Through the years, Denise is known as a race car driver, writer/editor — she founds Autoweek — and adventurer. Her friends and peers know her as a participant in life and in 2001, Denise McCluggage becomes the only journalist ever inducted into the Automotive Hall of Fame.

Alice Huyler-Ramsey, Car Enthusiast

22-year-old mom and housewife, Alice Huyler-Ramsey gets a Maxwell automobile from husband, John, after a motorized “monster” spooks her horse. By summer, she’s traveled 6,000 miles around her Hackensack home. At an endurance race, a Maxwell representative marveling at Alice’s driving has an idea — an all-expense paid road trip across the U.S. to prove that anyone, even a woman, can drive a Maxwell. Sure, why not? Leaving 9 June 1909, Alice, with her two sisters-in-law and a female friend, arrives in San Francisco 59 days/3800 miles (and countless mechanical mishaps) later to become the first woman to drive across America. Seventeen years after her passing, Alice is inducted into the Automotive Hall of Fame in 2000 — another feminine first.

Mary Barra, Business Leader

Motor City runs in Mary Barra’s blood. Born in Royal Oak, Michigan, her father Ray works at Detroit’s Pontiac car factory and after high school, Mary attends what is now Kettering University. At 18, she gets a job at General Motors as a co-op student checking fender panels and inspecting hoods to pay for college. This is the start of Mary’s move through the GM ranks, earning first a Bachelor’s degree in electrical engineering at Kettering then a Master's in Business Administration from Stanford on a GM fellowship. By January 2014, Mary Barra is made CEO of GM — the first woman ever to lead an automobile manufacturer — determined to make the American carmaker as synonymous with tech as with vehicles.

Hedy Lamarr, Inventor

She is dubbed “The Most Beautiful Woman in the World,” the physical inspiration behind Disney’s “Snow White” and DC’s “Catwoman.” Then during World War II Austrian bombshell, Hedy Lamarr works with friend, avant-garde composer George Antheil to create a secret communications system to defeat the Nazis. They patent and share it with the U.S. Navy who ignores it until the 1960s. As her star fades, her technology rises, becoming the basis for Wi-Fi, mobile phones and GPS. In 1997, Hedy and George receive the Electronic Frontier Foundation Pioneer Award and the Bulbie Gnass Spirit of Achievement Bronze Award — Hedy being the first woman to do so — and are posthumously inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame in 2014.

Michelle Christensen, Auto Designer

Supercars are a man’s domain — or they were. As a student at ArtCenter in Pasadena, California, Michelle Christensen begins working on a class project that makes Acura recruiters sit up and notice. The innovative design lands her a rare position at the carmaker as the company’s first female exterior car designer upon her 2005 graduation. That “project” becomes the eye-popping 2010 Acura ZDX crossover leading the company to tap her as the first woman to design a supercar, overseeing the exterior design of Acura’s hugely successful crowd-pleasing 2016 NSX. Looking “fast even when it is parked,” Michelle’s design proves women and supercars are no longer mutually exclusive.

Jean Jennings, Journalist

It starts at the kitchen table, listening to her father — editor of Automotive News — talk cars. Jean Jennings is so enamored, she buys a used car, paints it yellow, adds a top-light and a meter then joins the Yellow Cab Company in Ann Arbor, Michigan, as an owner/operator… at 18. By 23 she’s working for Chrysler as a test driver, mechanic, and welder. Car and Driver Magazine hires Jean to write in 1980 and within five years she’s established Automobile Magazine as the first executive editor. But it’s her contributions as the GOOD MORNING AMERICA automotive correspondent, President and Editor-in-Chief of Jean Knows Cars, and on-air media darling across various outlets that earns her the label of “Queen of Cars.”

Shirley Muldowney, Racing

Shirley Roque falls for racer, Jack Muldowney, marrying him at 16. He teaches her to drive and she discovers she loves racing. With Jack upgrading her cars, Shirley enters drag race matches, becoming the first woman to receive a National Hot Rod Association (NHRA) license in 1965. By mid-’70s, she’s the first woman to win the NHRA Spring Nationals then the first racer ever to win three NHRA World Fuel Championships — 1977, 1980, 1982. She comes back from a near-fatal accident to win again in 1989 — retiring in 2003 with 18 NHRA titles. Not fond of the nickname “Cha Cha,” nor her biopic, “Heart Like A Wheel,” Shirley Muldowney embraces the label of “First Lady of Drag Racing”... because she’s earned it.

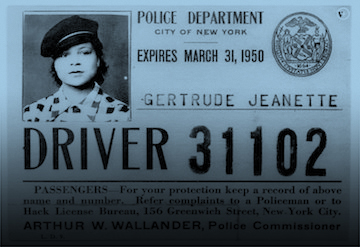

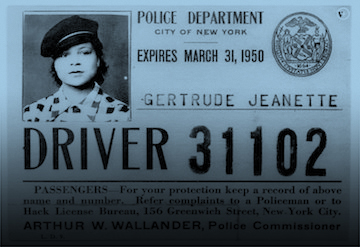

Gertrude Jeannette, Car Enthusiast

Marrying 35 years older heavyweight prizefighter, Joe Jeannette — sometime Paul Robeson bodyguard — at 18, Gertrude Jeannette becomes the first licensed female motorcyclist in Manhattan so she can ride with Joe’s motorcycle club, the Harlem Dusters. Looking to pay for speech class at the American Negro Theatre to correct a childhood stammer, Gertrude answers an ad for women to replace male cab drivers lost to the WWII draft in 1942, is the only one to receive her license, becoming the first licensed woman NYC hack (Joe finds out by reading it in the paper). Gertrude goes on to perform and write plays, leaves taxis in 1949, survives Blacklisting in the ‘50s, and achieves a theatrical career on par with her other “firsts.”

Lella Lombardi, Racing

What if unassuming, private, Lella Lombardi hadn’t taught herself to drive the family butcher shop delivery van because her parents didn’t know how? What if she didn’t buy her first car at 24 and start paying her own way in races, becoming known as the “Tigress of Turin?” What if she didn’t become the first woman in 17 years to qualify for a championship F1 event? What if she wasn’t the only woman to collect championship points in an F1 championship race, finishing sixth in the 1975 Spanish Grand Prix? And what if her pit crew had overlooked her gender and believed her when she said her cars had performance problems, thereby helping her break down less and win more? What if indeed.

Florence Lawrence, Inventor

Florence Lawrence stars in almost 300 films, is called “The First Movie Star,” yet few know of her. By 1904, she’s earning $500-a-week from a company refusing to put her name in the credits and is called “The Biograph Girl.” Her weekly salary — $14,112.00 today — allows an expensive passion — motorcars. Florence adores driving, is her own mechanic, and realizing drivers can’t easily signal direction or braking, invents the first turn signal — push a button on the dash to raise or lower a direction arm — and brake signal — press the brake and a small “STOP” sign pops out of the rear bumper. She patents neither, however, dying the year before Buick installs turn signals as standard.

Elsa Foley & Marlene Mendoza, Automotive Engineers

There’s an all too distressing driving phenomenon — hot car syndrome (37 children a year die on average). After mom, Marlene Mendoza leaves a lasagna in her backseat overnight it gets her thinking about forgotten kids. So, she and co-worker, Elsa Foley put their heads together. The two are uniquely positioned to discover a solution as members of a small, elite group — female engineers in the automobile industry. Working together at Nissan, they design the Rear-Door Alert System, which tracks rear-door usage and alerts the driver — first by dashboard text then horn chirps — to check the backseat when completing a trip. The system is on eight 2019 Nissan models and will become standard on all four-doors by 2022.

Helene Rother, Auto Designer

Leipzig-born artist Helene Rother enters the Paris fashion scene in the 1930s, quickly making a name for herself. By decade’s end, the Nazis force her to flee with her seven-year-old daughter to — wait for it — Casablanca. She gets them to New York where Helene works for Timely Publications (later Marvel) before joining General Motors (GM) in Detroit designing car interiors. She is the first female automotive designer and makes a staggering — male envy-inducing — $600-a-month ($9,243.20 today). Four years later, Helene opens her own design studio, landing the Nash-Kelvinator account, garnering them the coveted Jackson Medal for outstanding design and opening the door for all female auto designers after her.

Joan Newton Cuneo, Racing

Free-spirited Joan Newton marries wealthy Andrew Cuneo who buys her a Locomobile in 1902. By 1905, Joan services her own car and enters the inaugural 1905 Glidden Tour — an 870-mile race starting in New York City. After crashing and banned from ascending New Hampshire’s Mount Washington because race sponsor, American Automobile Association (AAA), declares it “too dangerous” for her, Joan finishes. By 1908, she achieves a perfect score of 1,000, the only competitor to drive Glidden’s entire now 1,570 miles themselves. AAA bans women from their events in 1909 and “the woman who got women banned from racing”— the first notable female racer in America — goes quiet after setting the women’s speed record in 1911.

Wilma K. Russey, Car Enthusiast

Discovering Wilma Russey is like learning unicorns are real. First, she’s hired as an auto mechanic at Dalton’s Garage in New York City in 1914. Then, she becomes the first woman taxi driver in the city on New Year’s Day, 1915. Wearing a skirt, leopard-skin hat and stole, long black leather gloves, a brown duster and high tan boots, Wilma parks at Broadway and Fiftieth, attracting not only onlookers but the attention of the New York Times. Her first customers are two young men who want to be taken down the street to say they were her first. Once satisfied, they get out, pay their fare and tip generously. With her mechanical know-how, upkeep of Wilma’s car is a cinch and word spreads.

Mary Anderson, Inventor

On a visit to wintry, snowy NYC, Alabama native, Mary Anderson notices her streetcar driver constantly opening the split windshield to wipe it clear, drenching himself and those around him. She returns home and sketches an idea for the very first windshield wipers — manually operated by a switch inside the car and removable for fair weather. She is awarded a patent in November 1903 and submits her idea to various automakers. There are no takers. Her patent expires and in 1922, Cadillac makes windshield wipers standard on all of its cars and they're soon required on all vehicles. Mary never sees a dime from her invention but is inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame in 2011.

Charlotte Bridgwood, Inventor

In the Urban Dictionary, “bridgwood” means: “Apt and wise, close to genius;” and based on Charlotte Bridgwood. Tired of manually operating the windshield wipers designed by Mary Anderson in 1905, Charlotte develops and patents electrically powered rollers in 1917. The former vaudevillian known as Lotta Lawrence owns Lawrence Dramatic Company in Toronto, Canada, and is mom to “The First Movie Star,” Florence Lawrence. Love of automobiles runs in the family as does not being recognized for inventions that forever change the automotive industry. Lotta patents her wipers — making them in her Bridgwood Manufacturing Company — but automakers aren’t interested. Her patent expires in 1920, and Cadillac makes automatic wipers standard on all models two years later — a very bridgwood decision.

Dorothée Aurélie Marianne Pullinger, Automotive Engineer

Dorothée Pullinger starts as a 16-year-old draftsperson for Scottish automotive company, Arrol-Johnston in 1910. The company switches to airplanes for WWI and she becomes supervisor of England’s Vickers munitions factory overseeing women manufacturing explosive shells. Dorothée returns to Scotland at war’s end to the renamed Galloway Motors Ltd., as the lead on the only car ever designed specifically for women. A shrewd businesswoman and keen race driver who wins the 1924 Scottish Six Day Car Trials cup, Dorothée — a founding member of the Women’s Engineering Society — is inducted into the Scottish Engineering Hall of Fame in 2012.

Mercédès Jellinek, Muse

She doesn’t invent anything; never owns an automobile, but Mercédès Jellinek inspires one of automotive’s iconic brands. Her father, Austro-Hungarian businessman, Emil’s fascination with the horseless carriage makes him push Daimler-Motoren-Gesellschaft (DMG) to create faster, stronger cars, entering races under the pseudonym, Mr. Mercédès. When he promises to buy 36 of the new models himself at a cost of $130,000 in 1900 ($3.9 million today) in exchange for being exclusive sales agent for DMG and naming the cars after his beloved daughter, DMG says, “Okay.” The cars are so good they kick France out of the top racing spot, signaling “the Mercedes age.” Emil even changes the family name to Jellinek-Mercedes, and the vehicles that bear Mercédès’ name thrive to this day.

Michéle Mouton, Racing

Michèle Mouton is invited to rally races by driver Jean Taibi who soon makes her co-pilot but Michèle’s dad buys her a car and pays for one solo season to see what happens. She finishes 8th at Tour de Corse in women’s then 12th overall, becoming the French and European ladies’ champ. She wins the Tour de France rally in 1977, makes driver Ari Vatanen eat his “Never can nor will I lose to a woman” remark by overtaking him to win the World Rally Championship in 1981 — the first for women — then takes Pikes Peak in 1985, besting Al Unser, Jr.’s record by 13 seconds. Considered motorsport’s most successful ever female driver, legend Niki Lauda calls her a “superwoman.” Yep.

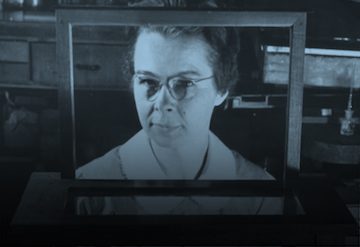

Mildred Dresselhaus, Inventor

Mildred “Millie” Dresselhaus — dubbed “The Queen of Carbon” — predicts the existence of carbon nanotubes — used in automotive parts, rechargeable batteries and more — the basis of nanotechnology. A child of the Great Depression, the Bronx native attends Hunter College, receives a Fulbright Fellowship to spend a year at Cavendish Laboratory, Cambridge University, and earns both a Master’s then a Ph.D. An avid musician — she studies on scholarship as a child — Millie is the first woman made a fully tenured MIT professor, where she teaches for 57 years, the first woman to win the National Medal of Science in Engineering and earns the Medal of Freedom — the highest civilian honor in the U.S. — in 2014.

Odette Siko, Racing

POOF! Odette Siko enters the 1930 24 Hours of Le Mans as her first official race with Marguerite Mareuse. Hard to believe, true, but Odette’s origins are a mystery and the duo become the first women — separate and together — to compete. They finish 7th overall, shocking everyone, and 9th in 1931 then disqualified for misunderstanding a pit signal. By 1932, Odette comes in 4th overall with a different co-driver, a record for women at Le Mans still unbroken, then sets and breaks ten endurance records and fifteen records in Group C International racing on an all-woman racing team — some records remain today. In 1939 Odette finishes 18th at the Monte Carlo Rally with Louise Lamberjack, and vanishes. POOF!

Maria Teresa de Filippis, Racing

Maria Teresa de Filippis is goaded into racing by her three older brothers and is instantly besotted. The only woman to enter hill climbs in Southern Italy earns three class wins and three class seconds. She wants Formula 1 and in 1958 becomes the first woman to enter a World Championship Grand Prix in Monaco then places 10th at the Belgian Grand Prix — the first woman to compete in and finish a Formula 1 race. Prevented from entering the French Grand Prix by the race director — “The only helmet a woman should wear is the one at the hairdresser’s” — the deaths of her closest companions devastate the first woman in Formula 1 and it’s 20 years before Maria Teresa races again.

Vivien Keszthelyi, Racing

Vivien Keszthelyi enters her first race at 13, finishing 4th in juniors and fastest female overall. The promoter of the Swift Cup Austria championship notices and Vivien enters, beating adult men to come in 4th — still only 13. The next season, she’s 1st in women and 3rd in absolute before switching to FIA Central European Zone Trophy driving, becoming a two-time Hungarian champion at 15. By 2018’s end now 17-year-old Vivien wins the rookie category and overall vice-champion. BlackArts Racing taps her as their official driver of the 2019 Winter (W) Series, races designed to bring talented women drivers into coveted Formula 1. Looks like Vivien — the youngest and first female Hungarian Formula 3 driver — is just getting started.

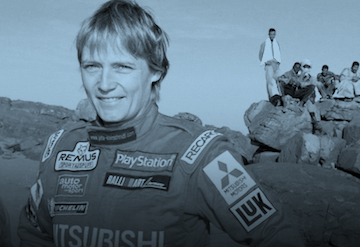

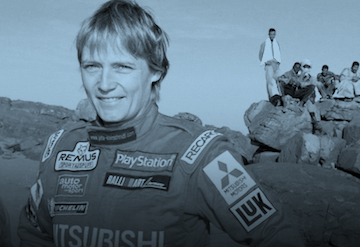

Jutta Kleinschmidt, Racing

Jutta Kleinschmidt buys her first motorcycle at 18 and soon begins racing. After earning a degree in physics and working for BMW’s R&D department as an engineer, she pursues her dream of professional racing full time. She first enters the grueling Paris-Dakar Rally with a motorcycle in 1988 then again in 1992 and 1994. She switches over to cars in 1995 and helps develop what will become the most successful rally vehicle, the Mitsubishi Pajero Evo, becoming the first and only woman to win the Paris-Dakar Rally in 2001. By the time she hangs up her rally helmet in 2007, Jutta has come in the Top 5 six times and goes on to fly/own helicopters while appearing as a motivational speaker.

Maude M.A. Yagle, Entrepreneur

Maude Yagle looks like a kindly schoolteacher or someone’s loving mom. Imagine everyone’s surprise when she buys the car formerly owned by late racecar driver, Frank Lockhart in 1928. She hires Ray Keech to compete and uses the name M.A. Yagle to avoid male backlash. Her car wins three out of six races that season, coming in 4th at Indy 500 due to mechanical failure. Then at the 1929 Indianapolis 500, Ray wins, making Maude “M.A.” Yagle — who’s not allowed in the garage or pit section, so manages racing details from the grandstands — the first and only woman to win the coveted competition as a car owner. And in her 1968 obituary, it’s never mentioned.

Dorothy Levitt, Car Enthusiast

Britain’s response to Camille du Gast, Dorothy Levitt — born Elizabeth Levi — ditches an arranged marriage for Paris with racecar driver Selwyn Edge. She works her way from car cleaner to chauffeur of Selwyn’s cars, then returns to England to teach women to drive, instructing royalty and aristocracy. The first English woman to race in 1903, Dorothy dresses to accentuate her femininity while breaking women’s speed records, moves from cars to boats and planes, and writes her 1909 feminine car bible, THE WOMAN AND THE CAR: A CHATTY LITTLE HANDBOOK FOR WOMEN WHO MOTOR OR WANT TO MOTOR — still chatty and selling today. By 1910, Dorothy retreats from public life only to be found dead in her bed in 1922 at age 40.

Keiko Ihara, Racing

Keiko Ihara enters racing handing out trophies while wearing swimsuits. She starts driving in 1999, debuting at the Ferrari Challenge Japanese Championship, winning MVP then 2nd place at the World Finals. After earning the same trophies she once handed out, Keiko enters the 24 Hours of Le Mans — the first Asian woman — three times, wins the 4 Hours of Fuji in the Asian Le Mans Series in 2014 then becomes the first woman in World Endurance Championship (WEC) history to win a place on the podium by coming in 3rd at the 6 Hours of Fuji. She’s also Outside Director for Nissan, teaches English to Japanese kids, member of the FIA “Women in Motorsports,” Sports Ambassador for… you get the point.

The Speed Sisters, Racing

They’re the Middle East’s first all-women racing team. They drive in brutal and heavily male-dominated Palestinian street racing — aka drift racing. They fold themselves into everyday VW’s, Peugeots and BMW’s with souped-up engines and stripped down interiors, pull donuts and kick butt. Their cars reflect who they are and their struggle to overcome obstacles on their own terms. They started with 8 members and are now down to 4 plus a manager. They hear things like “you should be in the home cooking” and face Islamic cleric backlash. But manager Maysoon Jayyusi, and drivers Mona Ennab, Marah Zahalka, Noor Dauod, and Betty Saadeh — with a huge male following cheering them on — just keep driving.

Amna Al Qubaisi, Racing

Racing firsts run in her family. Dad Khaled Al Qubaisi is the first Emirati to compete at the 24 Hours of Le Mans and at 14, Amna begins kart racing, becoming the first Arab female race driver. By 16, she’s earning international top 10 finishes, the first female Emirati to win the UAE RMC Championship and the first woman ever sponsored by Kaspersky Lab. Amna’s selected by the Automobile & Touring Club of the UAE (ATCUAE) to represent UAE at the GCC Young Drivers Academy Programme — again a feminine pioneer — winning it. In 2018 — six months after the female driving ban is lifted in Saudi Arabia — 18-year-old Samna’s tapped by Envision Virgin Racing team to test drive Formula E.

Reem Al Marzouqi, Inventor

Reem Al Marzouqi gets the idea for her unique car design by watching a television special on Jessica Cox, the world’s first licensed armless pilot operating her plane with just her feet. “What if…?” Reem thinks. What if those who can’t use their upper extremities could now drive themselves through technology? She goes about developing the first car ever designed to be driven without the use of hands or arms. All is controlled by foot levers suddenly making automobile driving attainable. The United Arab Emirates University (UAEU) in Al Ain student applies for a U.S. patent on her innovative car in 2008. Five years later, Reem becomes the first UAE citizen ever awarded such an exclusive right from America.

Desiré Wilson, Racing

Desiré Wilson — daughter of South African motorcycle champion, Charles Randall — begins racing at age 12 in midget cars. In 1976 she earns a “Driver of Europe” scholarship, racing Formula Ford and Sports 2000’s. Her sights set on Formula 1, Desiré moves to Europe where Brands Hatch racetrack owner, John Webb, becomes a fan and supports her as she pushes toward her goal. By 1980, after false starts, almosts and equipment failures, Desiré achieves the unimaginable at Brands Hatch — becoming the first and only woman to win a Formula 1 race. The track names a grandstand after her and Desiré goes on to become the only woman licensed to drive in a CART Indycar event and to hold an FIA Super license.

Manal Al Sharif, Entrepreneur

In 2011, Manal Al-Sharif does the unthinkable — films herself driving in Saudi Arabia, defying the only country with the law against “driving while female.” It is the first such protest in over 20 years. The woman’s rights activist puts the film on YouTube and is jailed for nine days. The arrest gains attention, but her ultimate price goes far beyond time served. Manal loses custody of her son, her job, and her home. She picks herself up, moves to Sidney, Australia, remarries, has another son and continues to fight. Her sons have never met, Manal still deals with backlash, but her strength pays off when in 2018, the decades-long ban on “driving while female” is lifted.

Camille du Gast, Car Racing

Camille du Gast is widowed at the age of 27 and already ahead of her time. After watching the 1900 Gordon Bennett Cup race, Camille buys a Peugeot and Panhard et Levassor, is the second woman to get a French driver’s license and is one of two women to enter the Paris-Berlin race. She starts at the very back of 122 entrants in an inferior car but finishes in 33rd place. By 1904, France has banned women from motorsports, and Camille moves on to racing boats. After winning one race by default, the wealthy matron thwarts an assassination attempt by her own daughter, turns her attention to humanitarian causes, and becomes one of the most prominent French activists of the early 20th century.

Stephanie Kwolek, Inventor

Once entertaining a career in fashion, Stephanie Kwolek pursues and receives a degree in chemistry from Margaret Morrison Carnegie College in 1946. She plans on becoming a doctor, taking an interim chemist position with DuPont. The company’s polymer research fascinates her, however, and Stephanie forgets medical school. In 1965 she is tasked with finding the next generation of fibers that can withstand extreme conditions and discovers that under certain circumstances large numbers of polyamide molecules line up in parallel to form cloudy liquid crystalline solutions. Instead of rejecting the liquid, Stephanie spins it, creating fibers that are stronger and stiffer than anything in existence. It is Kevlar and it goes on to be used for everything from bulletproof vests to tires.

Mi Mi Vandermolen, Innovator

Netherlands-born Mimi Vandermolen graduates Ontario College of Art and Design in industrial design, going on to become the first full-time female automotive designer at Ford Design Studio in 22 years in 1970. While she is integral to designing both the revolutionary 1974 Mustang II and 1975 Granada, her role on“Team Taurus,” the crew behind the game-changing ergonomically designed 1986 model — the number one selling car in the U.S. at the time — and her first start-to-finish design of the second-generation 1993 Ford Probe make history. Using threats of dressing her male crew members in skirts and making them wear fake nails to understand women’s needs, Mimi changes the face of auto design forever.

Katharine Blodgett, Inventor

You're driving late at night or one sunny afternoon and you see a car coming your way. Their windshield's non-reflective, absorbing rather than bouncing the glare of your headlights or the sun back into your eyes. Thank Katherine Blodgett, the first female scientist hired by General Electric (GE) and the first woman to receive a physics Ph.D. from Cambridge University in England. Daughter of GE’s patent attorney, George Blodgett — murdered before she is born — Katharine’s education is encouraged by her father’s friend, GE scientist Irving Langmuir. Working as Langmuir’s research assistant, vibrant and cheeky Katharine discovers non-reflective glass, first for use in photo lenses then practical application in all number of vessels.

Liu Qing, Business Leader

Daughter of technology company, Lenovo, founder, Liu Chuanzhi, Liu Qing (aka Jean Liu) becomes enamored with computer science after reading Bill Gates’ book, THE ROAD AHEAD. A Harvard Master’s later, she’s at Goldman Sachs — after 18 rounds of interviews including a request to sing Celine Dion’s, “My Heart Will Go On” from Titanic. After 12 years, she joins Didi Dache as COO, in charge of the new transportation service, Didi Black. Jean is soon president and leads a merger with rival Kuaidi Dache, creating Didi Chuxing. She expands the services to include ride-sharing and bus when Uber comes calling and Jean, having built relationships with Lyft, Grab, and Ola, buys Uber’s China operations, making Didi Chuxing the largest mobile transportation platform in the country.